by Maria

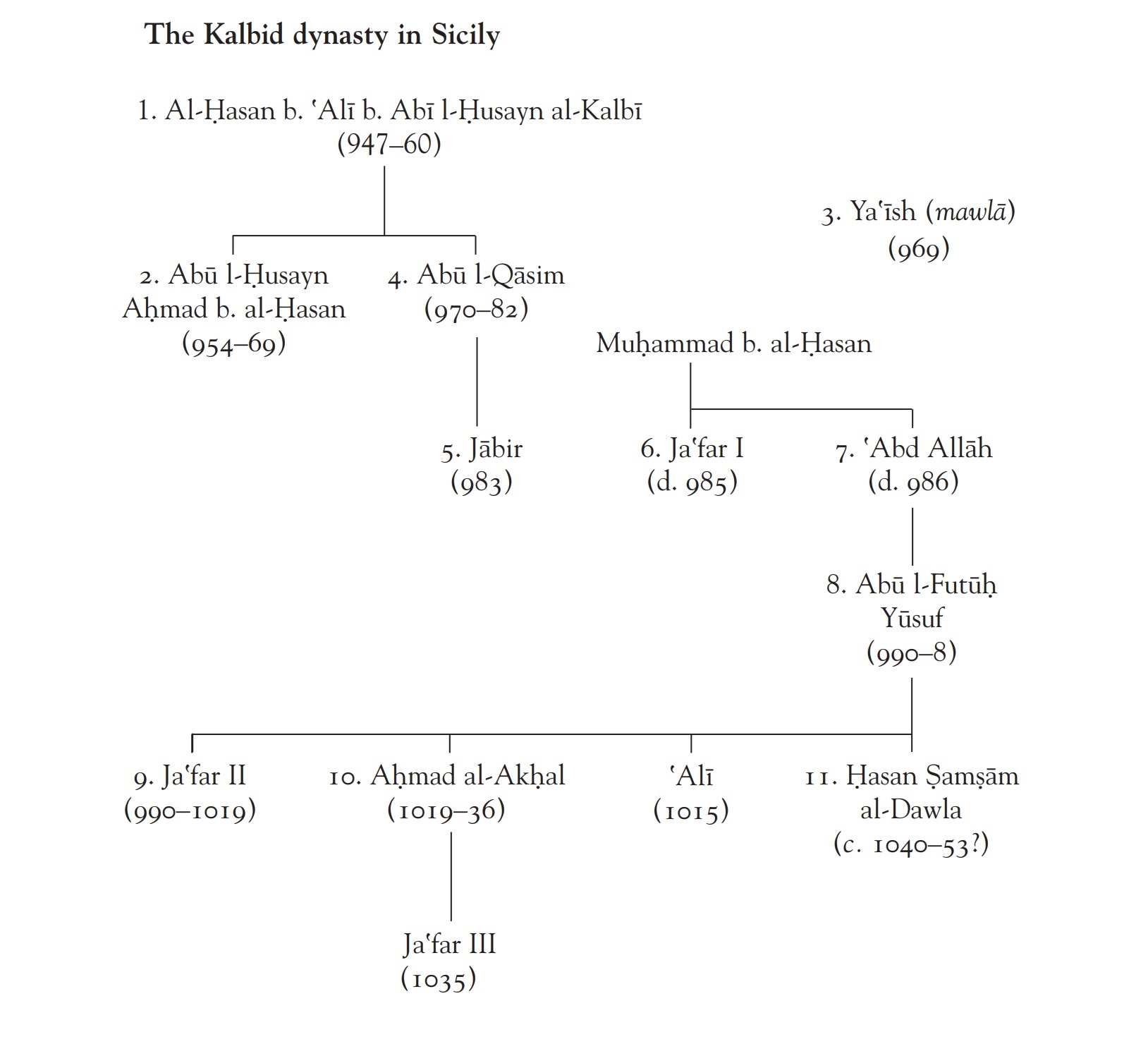

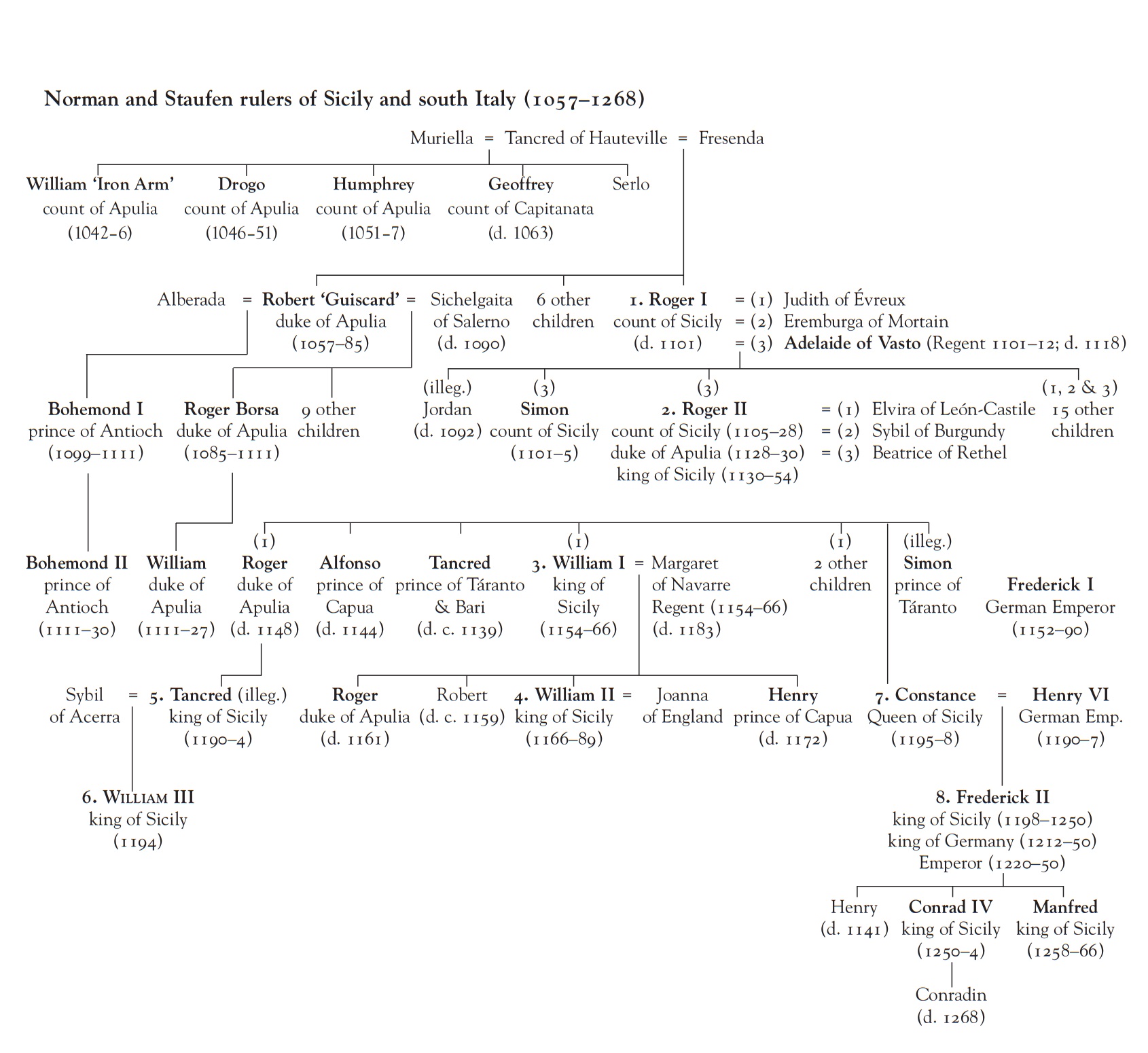

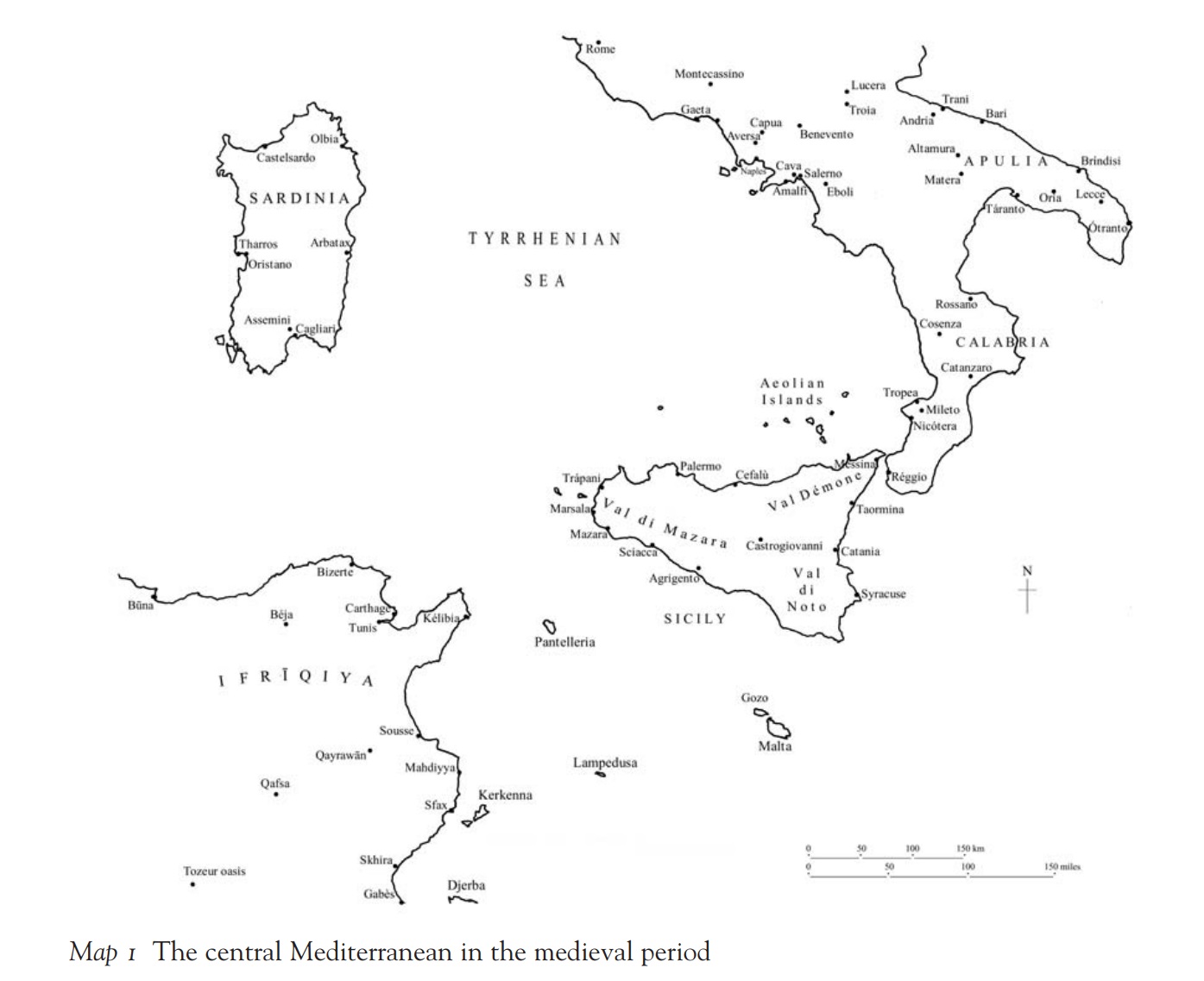

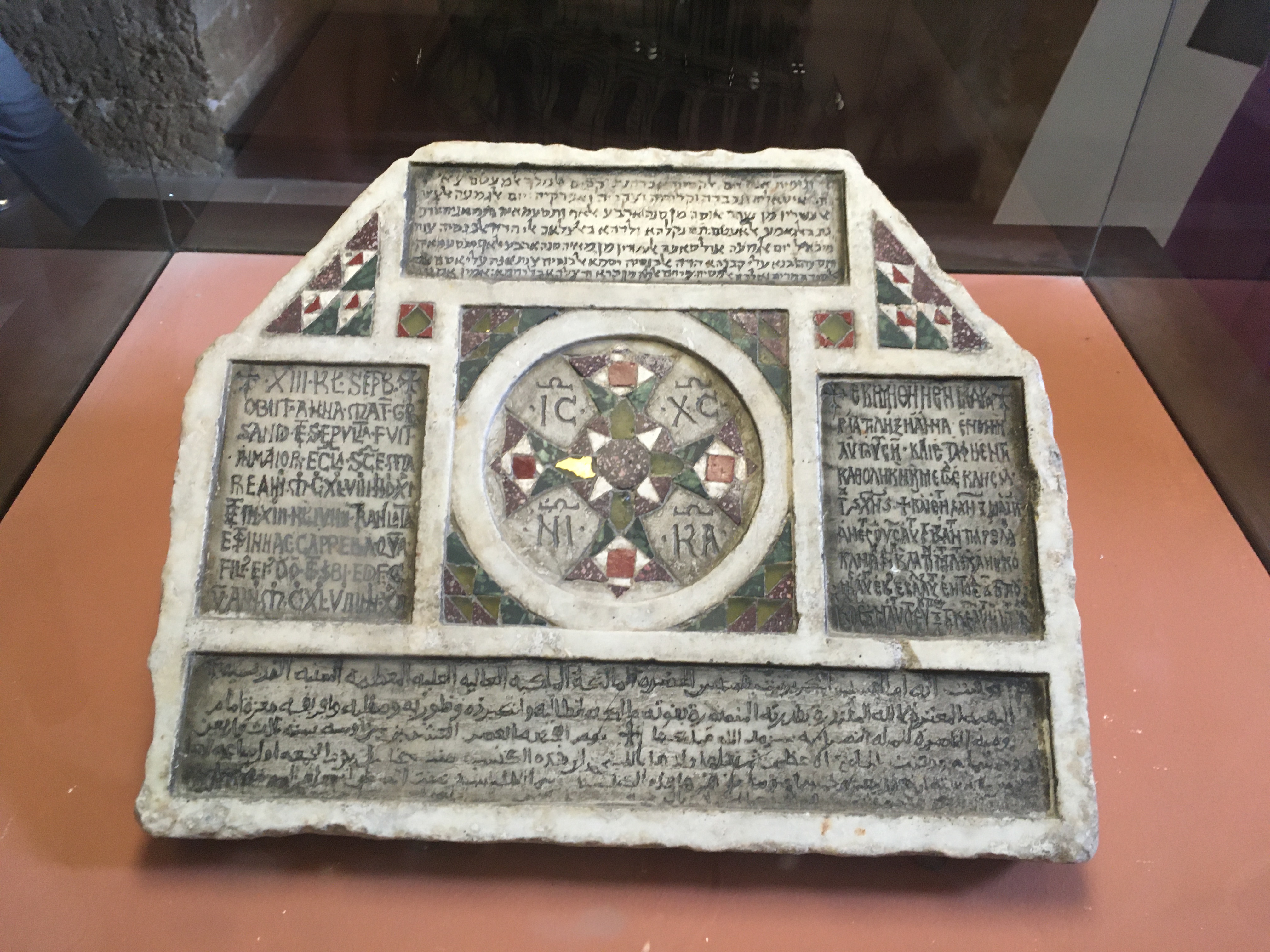

Perhaps the greatest challenge in developing something new, particularly religion, is that little we humans invent is truly novel and creative. After all, we are not (by most popular standards) deities ourselves, hence the search for an explanation to the hypercreative existence that is our world. Anyone who seeks to share a “new” unpopularized thought or establish a culture must do so using the same physical and linguistic ephemera that anyone else has. Consequently, this makes it difficult to distinguish where one group ends and another begins if, for example, artistic styles are too similar, or if rituals evolved out of and still bear strong resemblance to the “original.” 1 The religious student uses categorization labels like “Christianity” and “Islam” so that we may communicate effectively, but the scholar must begin to question when/where the line gets drawn around a community and if it is always a productive approach. This is particularly salient when studying history, as the surviving documentation rarely represents a cohesive view of the nuances of how people understood themselves within and between societal structures.2 In a place like medieval Sicily, where numerous heritages cohabited a space and (re)defined their identities in close intimacy with others, we would be wise to consider such points of Dr. Nancy Khalek of Brown University in her publication Damascus after the Muslim Conquest.3 Sicily’s Cappella Palatina and Palazzo Chiaromonte-Steri are quintessential instances of the scholarly dilemmas of certainty in taxonomy because of their inherent multicultural origins and the disagreement over how much we really know about them.

Inside the Cappella Palatina

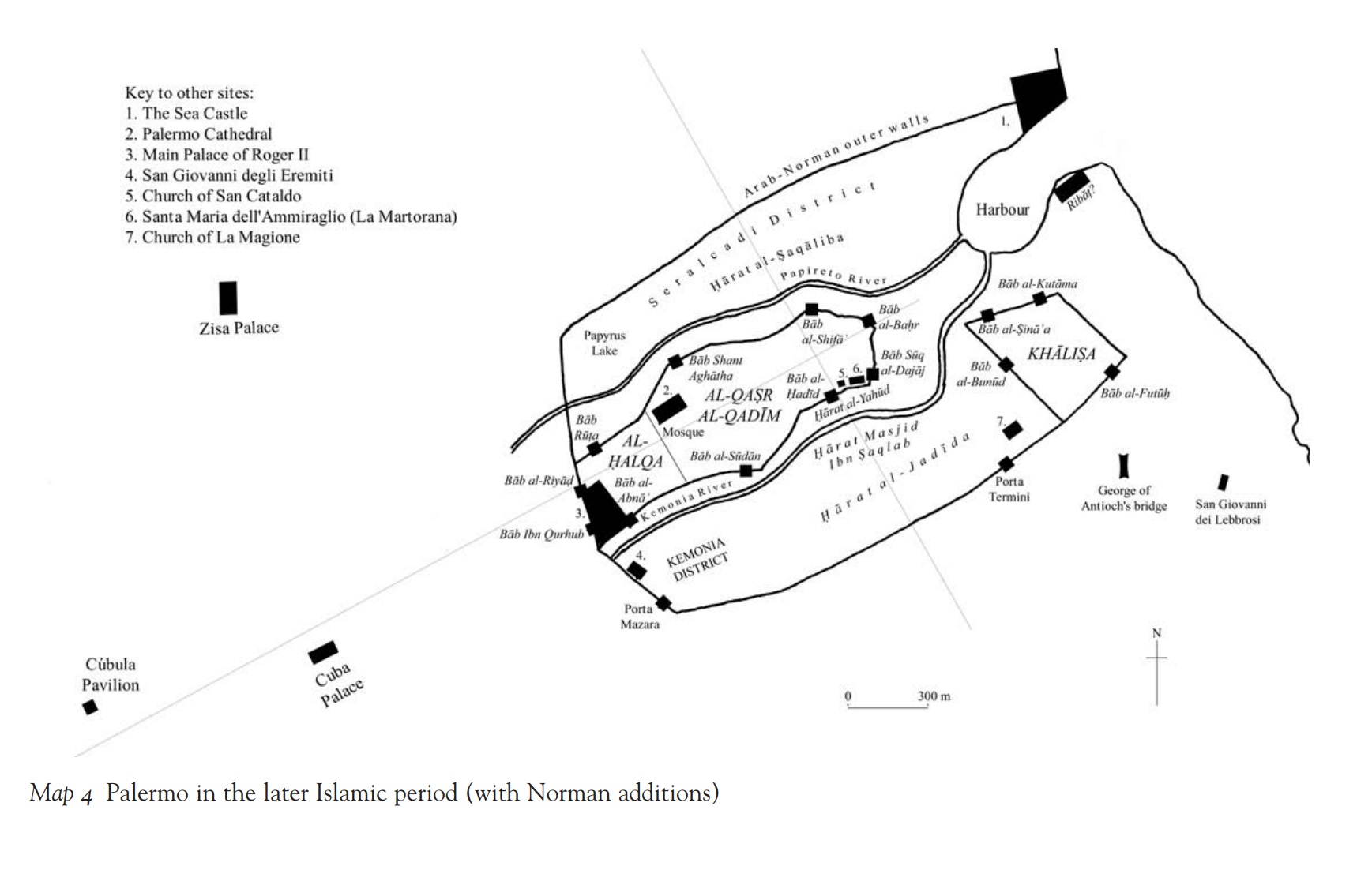

“If the Umayyads were good at anything, they were good at communicating to an audience,” Dr. Khalek writes of one of the first, largest Muslim caliphates to emerge after the time of Muhammad.4 We can corroborate this throughout history with other memorable leaders: Those who communicate charismatically amass more respect and power. But communication is also nonverbal and passive, as in the case of art and architecture. She continues: “…architectural sophistication was not the exclusive purview of a community to which [the caliph] did not belong: it was simply up to him to adapt to his environment in order to command the respect of his diverse subjects. Later caliphs were similarly concerned with issues of legitimacy…” 5 In other words, were they concerned with the design of their buildings because they appreciated architecture or cared more about what it said about their wealth and influence? The question can also be fairly asked of King Roger II in Sicily, whose greatest construction is arguably his Cappella Palatina, or palatine chapel. The marvelous structure still glitters with gold, Byzantine mosaics as well as an Islamic muqarnas ceiling unique to Europe, likely made by traveling artists.6 These features would have communicated different messages to the different visitors in the space. It is undoubtedly a show of power, for who could afford something so golden and foreign but a legitimate king? Who could mesh together these seemingly adverse traditions but someone so much in God/Allah’s favor to transcend them? The muqarnas ceiling is interestingly decorated with Christian Biblical figures reimagined in a Muslim art style, the style that the artists would have known, that Muslim subjects would have recognized and Christian subjects would have marveled at for its “newness.” 7

A close-up of a mosaic in the Cappella Palatina

Successors of Roger II continued to be inspired by this building, modeling their own constructions after it, and the scholarly dilemma becomes was the origin of this Sicilian style appropriation? Was he, a man of Norman/French origin, Muslim or Christian? Which group of his subjects were more important to him? Rather than try to definitively answer these inevitably loaded questions, Dr. Khalek argues, “…the emerging Islamic society in Syria was a product of its Christian and Byzantine environment in a fundamental sense, not simply because Muslims were borrowing ideas or blindly grafting onto their own old Arabian practices what other people were doing, but because they were cultural producers [emphasis added] in a world with which they were, and were becoming, increasingly familiar.” 8 Perhaps the inspiration-origin debate distracts from the creativity and motives that are more relevant to medieval studies. The fact is medieval Sicily was a uniquely diverse place situated between Europe and Africa, figuratively and literally. To gain legitimacy, Roger II had to present himself as ruler in a way that each of his peoples (Greeks, Latins, Muslims, and Jews) would have recognized from their preconceptions.9 Similarly, “The early Muslim community, always a minority in early medieval Syria, developed its initial imperial identity in a Byzantine milieu. Muslim architects, artisans, and chroniclers drew upon material and literary forms that were meaningful in the Byzantine world… whether… physical monuments or textual compilations, made use of and elaborated upon images and tropes that resonated with the mixed Christian and Muslim population of the eastern Mediterranean.” 10

Byzantine style mosaics in La Martorana (ignore restoration portion on the right)

One of the aforementioned later constructions inspired by the Cappella Palatina was the Palazzo Chiaromonte-Steri, a mansion of a wealthy Sicilian family that originally came from Spain.11 Rather than decorate their textured ceiling with reimagined Biblical figures and some go-to fillers of the Islamic palatial cycle like stars, moons, musicians, and dancers as on the muqarnas ceiling; they depict mainly violent clashes of Christian crusaders and Muslims.12 This is particularly ironic and interesting because Sicily’s Frederick II, a descendant and successor of Roger II, was excommunicated three times because of his reluctance to participate in the Crusades.13 The art style may appear “Sicilian,” but the content is not; which in turn suggests that the family had vested interest in rewriting the past, aligning with the new Aragonese rulers who succeeded Frederick II, and making the country seem as if it had been eagerly Christian all along. Dr. Kristen Streahle of Cornell writes, “[By p]erpetually subjugating their enemy on the ceiling, these crusaders effectively displace historic papal hostility towards the island [including an eventual Crusade to the island itself] in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.” 14 Dr. Khalek cites a similar example: “…it remains unknown whether [the leader of the Umayyad caliphate] himself actually had any interest at all in curtailing the religious presence of Christians in the cities of Syria so soon after the seventh-century conquests, it is clear that later Umayyad caliphs and the scholars who wrote about them did have a vested interest in deliberately fashioning and refashioning memories of Christian-Muslim life in early Islamic Syria.” 15 In this analogy, the first caliph is to Frederick II as the later caliphs are to the Chiaromonte family.

Portion of the ceiling in the Steri

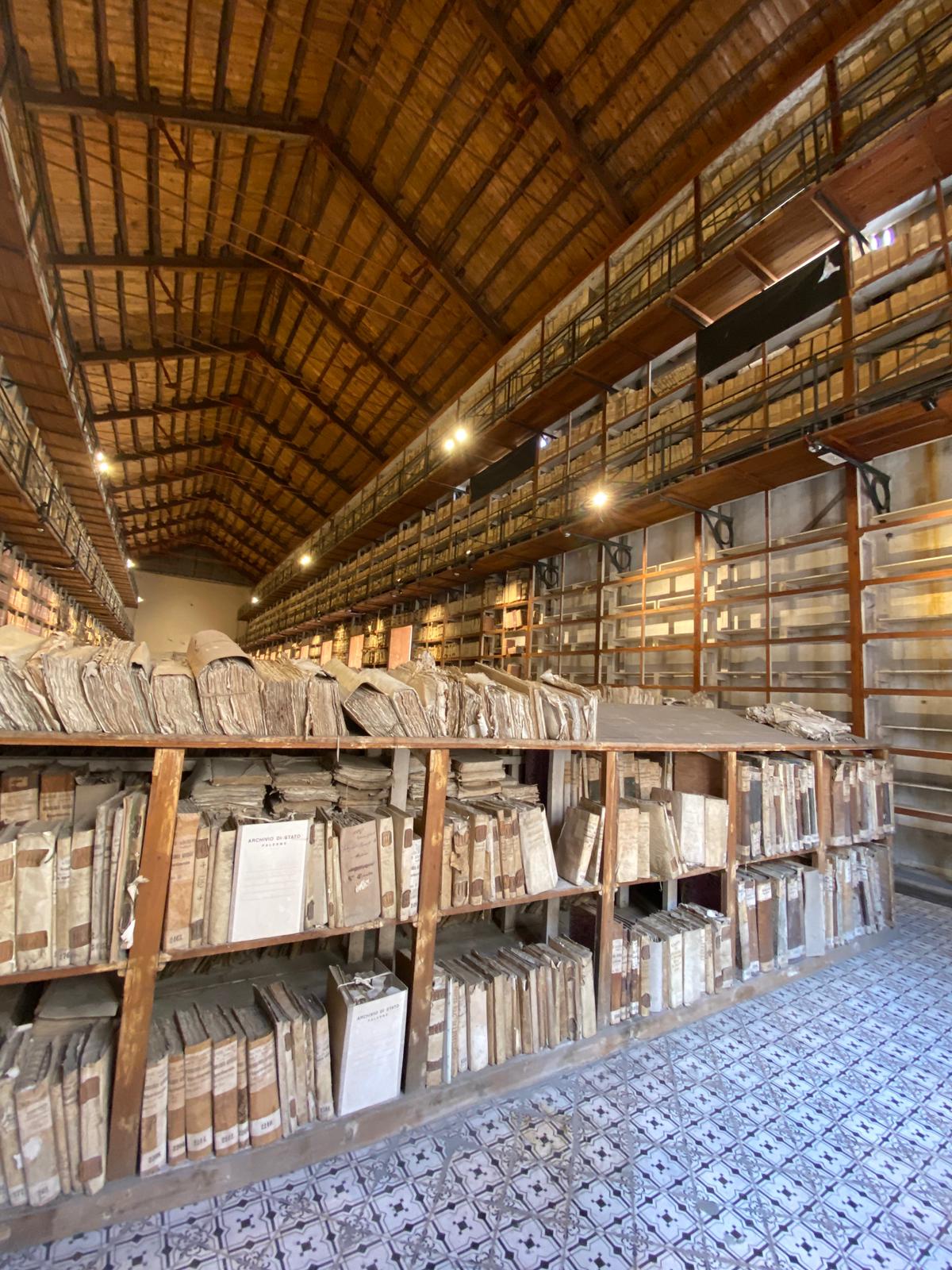

The debate that arises here is whether the focus was really on the formation of a firmer Christian religious identity or for the more practical reason, again, of amassing power. Dr. Khalek discusses the numismatic reforms of the Umayyads, how “…figural iconography’s replacement with purely calligraphic and allegedly more ‘orthodox’ decoration is generally seen as proof of a Muslim desire to erase and replace Byzantine models. One gets the sense that earlier… caliphs would have taken such measures much sooner if only they [could]… in fact, ‘on the economic side, the reform was not as all revolutionary but highly pragmatic.” 16 It was indeed highly pragmatic for the Spanish family to align with the pope and Aragons at this time, as they could (and did) gain power and influence. Another distracting debate is what Dr. Khalek calls “[a]n attentiveness to certainty.” 17 Chiaromonte influence blurred the history of the island’s Muslim and Jewish populations as the Inquisition they supported took effect (a jail was even in the backyard of this palazzo), and scholars often get caught up in disagreements over how much we can “know” from problematic, biased sources such as this one, which Dr. Streahle says was preserved because of its magnificence and creator’s influence.18 “…[M]ost contemporary scholars have placed at least as much emphasis (if not more) on confirming or discerning facts as we have on asking interesting interpretative questions.” 19 Perhaps a more productive approach is to acknowledge the incomplete nature of surviving evidence and move on. If the Steri survived because of humanity’s infatuation with the lives of the wealthy, we know we are missing accounts of marginalized civilian lives, and we know we cannot construct what medieval Sicily “was really like” for all who experienced it. We can instead focus on the brilliance of the multicultural artifacts that somehow were created and did survive and “try to situate those examples within a broader view.” 20

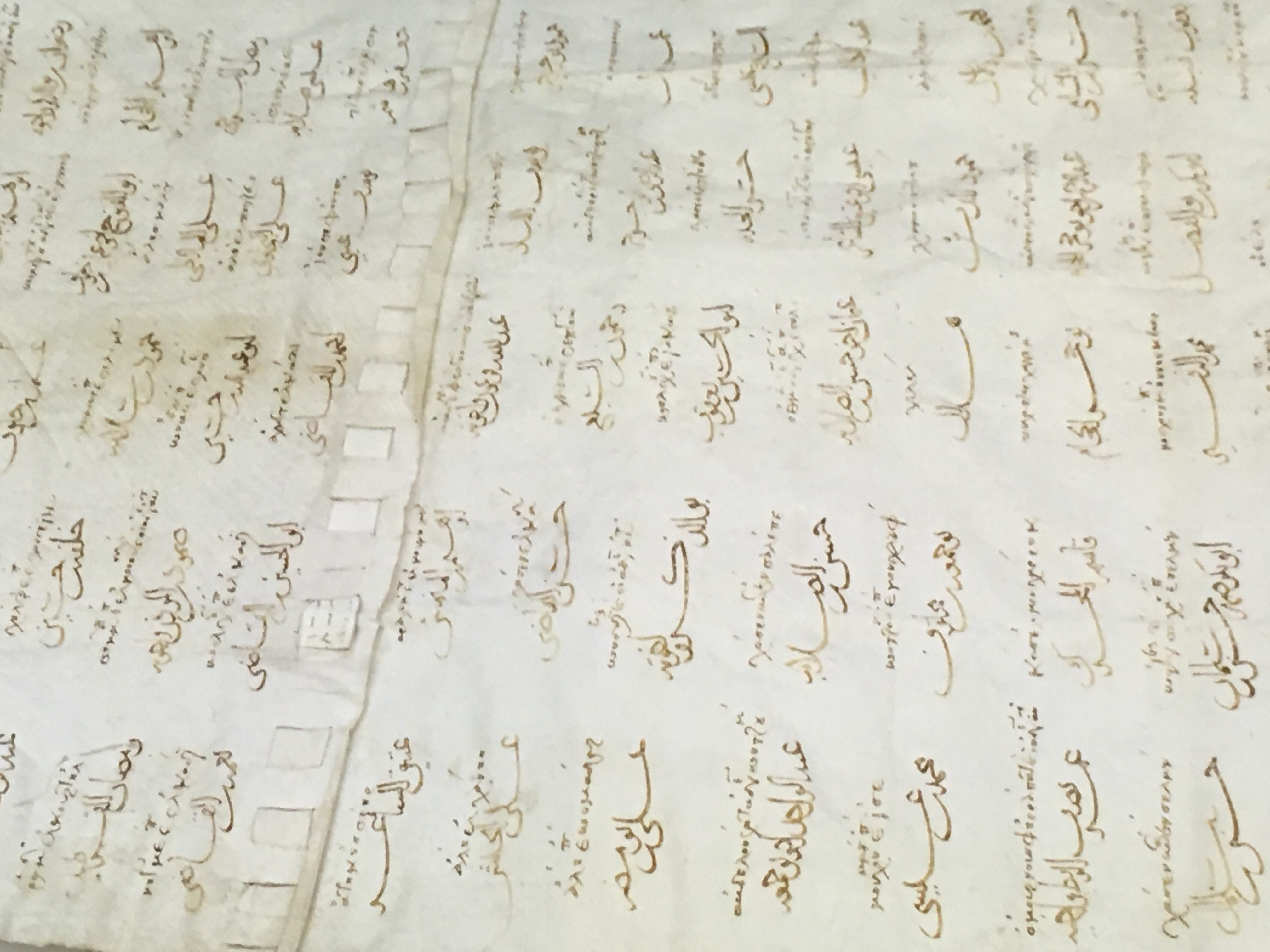

Census document from the Sicilian town of Cefalù written primarily in Arabic

Medieval Sicilian constructions are “concrete examples of cases that attest to the continuities and the changes” of identity development in the period.21 The diverse peoples who cohabited the island obviously influenced and inspired each other just as the people of Syria in the time of the birth of Islam. For the scholar to seek to categorize their experiences without significant qualification yields logical problems.22 A more advantageous process is to acknowledge the lack of surviving evidence and the fact that what did survive was likely due to its monetary and religious value, the latter of which must be mentioned as inextricably linked to the former. By cutting through certainty debates, we can transcend minutiae that we have no way to “prove” and instead get to the complex questions of how ancient peoples negotiated who they were in conversation with their neighbors in a way that is relevant to our globalized, divisive world today. Diversity is not new, and it is the scholar’s responsibility to find this precedent and a way to extrapolate enough from whatever survived attempts to erase it.

A column in the La Martorana church inscribed with Qur'an quotes